Succession of the Regency

When Horthy was elected Regent in 1920 the post was considered temporary, covering the term following the First World War until a monarch could ascend the thrown, therefore the question of the succession was not an issue at that time. On the 9th June 1937 the debate on the succession of the Regent began. According to the original draft - submitted by Prime Minister Kálmán Darányi and the Regent - after Horthy’s death Parliament could choose from his nominees - these names would be kept in a sealed envelope with the Holy Crown and watched over by three guards, until that time. However, members of Parliament suspected dynastic plans behind the bill and rejected it unanimously, such suspicions were unfounded.[1] The three nominees were Gyula Károlyi, István Bethlen [former PM] and Kálmán Darányi. But as MPs were not informed of the names of the nominees, the bill was only accepted with a modification, which allowed further nominations by Parliament.[2]

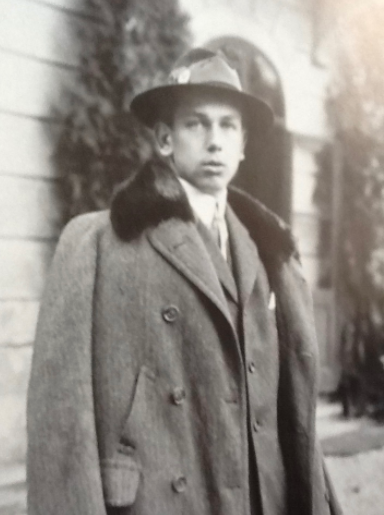

During the election, at Pentecost in 1939, the far right groups formed an alliance and got into Parliament in unprecedented numbers, frightening the moderates with their unaccustomed political tone and atmosphere. Archduke Albrecht Habsburg a member of the Hungarian branch of the Royal Family, youngest child and only son of Archduke Friedrich, had been aspiring for decades to the leadership of Hungary either as King or Regent. By the end of the 1930s he had become a supporter of Nazi Germany. At some point before the 17th June 1941 he tried to convince Berlin to support him in his aspiration to become Regent of Hungary.[3] Reacting to news of his activity in Berlin, maybe as early as the middle of May, a number of moderate lawyers were trying to find a way to elect the elder son of the Regent as his successor.

On the 22nd June 1941, Operation Barbarossa was launched and Germany crossed the Soviet border. Following an air raid on Kassa on the 26th June by unidentifiable aircraft, Hungarian forces joined the Operation in a de facto declaration of war. As a result of which, Archduke Albrecht lost his negotiating position in Berlin as Germany’s principle goal [Hungary entering the war] had been achieved. Meanwhile it was widely rumoured in the editorial offices of the capital that a committee had been formed to draw up a bill to ensure the election of Miklós Horthy’s son as his successor. It was further suspected that this committee was lobbying politicians and those in positions of influence. We have no evidence of who was involved in this campaign, however a witness, Herbert Pell, the American ambassador in Budapest, reported having been involved and confirmed the existence of the group.

Between the 8th November and the 23rd December1941, Regent Horthy was in the Siesta Sanatorium, according to daily reports of the National Broadcasting Company [MTI], suffering from ‘flu. According to rumours in Budapest at the time, initiated and fuelled mainly by Archduke Albrecht, Horthy was thereby threatening moderate circles with the possibility of his death to ensure support for his son’s succession. The same suspicion appears regularly in contemporary reports by the German secret service. [4]

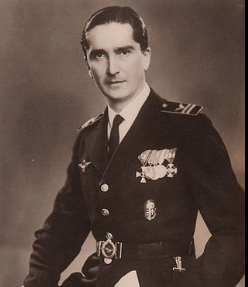

From the December of 1941, Hungary was at war against both the United States and Britain. István Horthy, more and more was seen to represent anti-Nazi feeling in his public appearances. This was no accident as it reflected the feelings of the moderates in the Regent’s closest circles. It was he who had said farewell with flowers to the departing American Ambassador at the station and had bought Pell’s American sports car, a famous feature in Budapest - driving it made his sympathy towards the US apparent.[5] It was conspicuous, after Pell’s departure, that remaining members of the US delegation stayed in the mansion of his wife’s family at Dísz Square, in the Castle District. We can assume that these were elements of a campaign aiming to turn the attention of the American government towards István Horthy as a possible partner in future negotiations. This assumption is confirmed in a letter to the British Foreign Office, written by Pell a few months later, supporting István Horthy. By the end of December the government had compiled a draft bill on the creation of the post of Vice Regent. According to a German Secret Service report, on one of the last days of 1941, while his father was still in the Sanatorium, István Horthy had a meeting with Prime Minister Bárdossy in which he gave his consent to the deletion of the right of succession from the draft, in return he asked the Prime Minister to give the right to the Regent to relinquish all elements of his authority at any time to a future Vice Regent. Taken together these indicators would suggest that, from his perspective, such an agreement could pave the way to his becoming a future negotiator representing Hungary in peace negotiations. On the 19th February 1942 he was elected Vice Regent under the terms of this agreement.[6]

Six months later, on the 20th August, he died flying a mission near the Russian town of Ilovskiy. As early as his funeral people were speculating about his successor, the most likely being the younger Count Gyula Károlyi, István Horthy’s brother-in-law who, unlike his family, had an excellent relationship with the Horthys. However, a few days after István Horthy’s funeral, on the 5th September, during a training flight in his Arado 79, Károlyi, together with his instructor, crashed into the Danube at Érd and both lost their lives. In January 1943, Soviet troops broke through the defence lines of the Germans and their allies on the River Don, in the face of unequal resistance they were able to advance ever closer to the Hungarian border. The question of a Vice Regency or the succession of the Regent was no longer relevant in Hungary. [7]

References

[1] Szinai-Szűcs 1962, 169 – 170.

[2] Thomas Sakmyster: Hungary’s admiral on horseback, 1918 – 1944, 1994, 194-195.

[3] Gergely Jenő – Pritz Pál: A trianoni Magyaroszág 1918-1945 Budapest, Vince 1998. Pg 27.

[4] Report from Walter Schellenberg, temporary head of RSHA ( Main Office of the German Security Service ) to the German Foreign Ministry, 20/12/1941, in: PA-AA Akten Inland II, Geheim R101158

[5] Peterecz Zoltán: Herbert C. Pell és Magyarország, in: Külügyi Szemle, 2011. 3. Szám, 583.

[6] Bern Andrea: Dinasztiialapítási kísérlet, vagy konzervatív összefogás? A kormányzóhelyettes-választás elvi, politikai hátttere, in: Visszatekintés a 19-20-ik századra, tanulmányok, főszerkesztő: Erdődy Gábor, ELTE Történettudományi Doktori Iskola, Új és Jelenkori Magyar Történeti Program, Budapest, 2011, 127-147.

[7] Ibid